The Uncomfortable Gaze: Reimagining the Portrait in the Age of Self-Curation

We no longer sit still.

To be painted once required patience, surrender, time. It demanded stillness, not only of the body, but of identity itself. The subject and artist entered a peculiar contract: to see and be seen, but never immediately. In contrast, today we are locked in a perpetual loop of curated visibility. With each tap, swipe, and filter, we publish ourselves. In the digital podium, portraiture has evolved, or perhaps devolved, into performance. What we now face is the uncomfortable gaze: not of others, but of ourselves, constantly edited and broadcast for consumption.

In the age of Instagram, where the portrait is no longer painted but uploaded, what has become of the soul of portraiture? Has it been lost to algorithms and instant gratification, or merely transformed? To ask this is to understand not only the shifting tools and techniques of portraiture, but the psychological states they demand.

Historical Portraiture: The Art of Stillness and Surrender

Original Portrait of Madame X before her shoulder strap was altered

When John Singer Sargent painted Portrait of Madame X, he was both a chronicler and a conjurer. His tools, brush, oil, canvas, were extensions of his eye, but they were also filters of time. The sitter, Madame Gautreau, submitted to hours of observation, exposure, and artistic manipulation of her soon to be tainted reputation. The result was not realism, but revelation. The portrait disclosed more than a likeness, it suggested myth, reputation, sexual politics. It scandalised Paris not because of what it showed, but because of what it implied.

Van Gogh Self Portrait

Van Gogh, by contrast, turned the gaze inward. In his self-portraits, we do not see performance; we see need. He paints himself not as he wants to be seen, but as he is, fragmented, desperate, furious with tenderness. His portraits are diaries of psychic pain, not advertisements. There is no audience in his mind, only urgency of expression.

In both men’s work, portraiture was a deeply human act, requiring submission to another’s interpretation. The artist’s brush became a moral lens: capable of distortion, yes, but also of profound empathy. These paintings, slow in creation and rich in implication, offered time not only for reflection, but for revelation.

The Selfie as Portrait: A Performance of Control

Fast-forward to the Instagram age. Here, portraiture is no longer the privilege of the elite, nor the craft of the few. It is democratic, ubiquitous, compulsive. Millions of faces flood the grid, each image designed not for contemplation but for recognition, reward, and reaction. Where Sargent once laboured over skin tone and posture, today's portraits are manipulated through filters and apps, contouring, brightening, smoothing. The face becomes a product, the gaze transactional.

This is not to say today’s self-curation lacks artistry. But it is a different kind of art, a performance not of truth, but of control. Whereas the historical portraitist had agency over the sitter’s image, the contemporary subject holds that power themselves. The result? A world where the subject is both painter and painting, both curator and commodity.

Tracey Emin sitting in front of her installation which earned her a “Turner prize” nomination

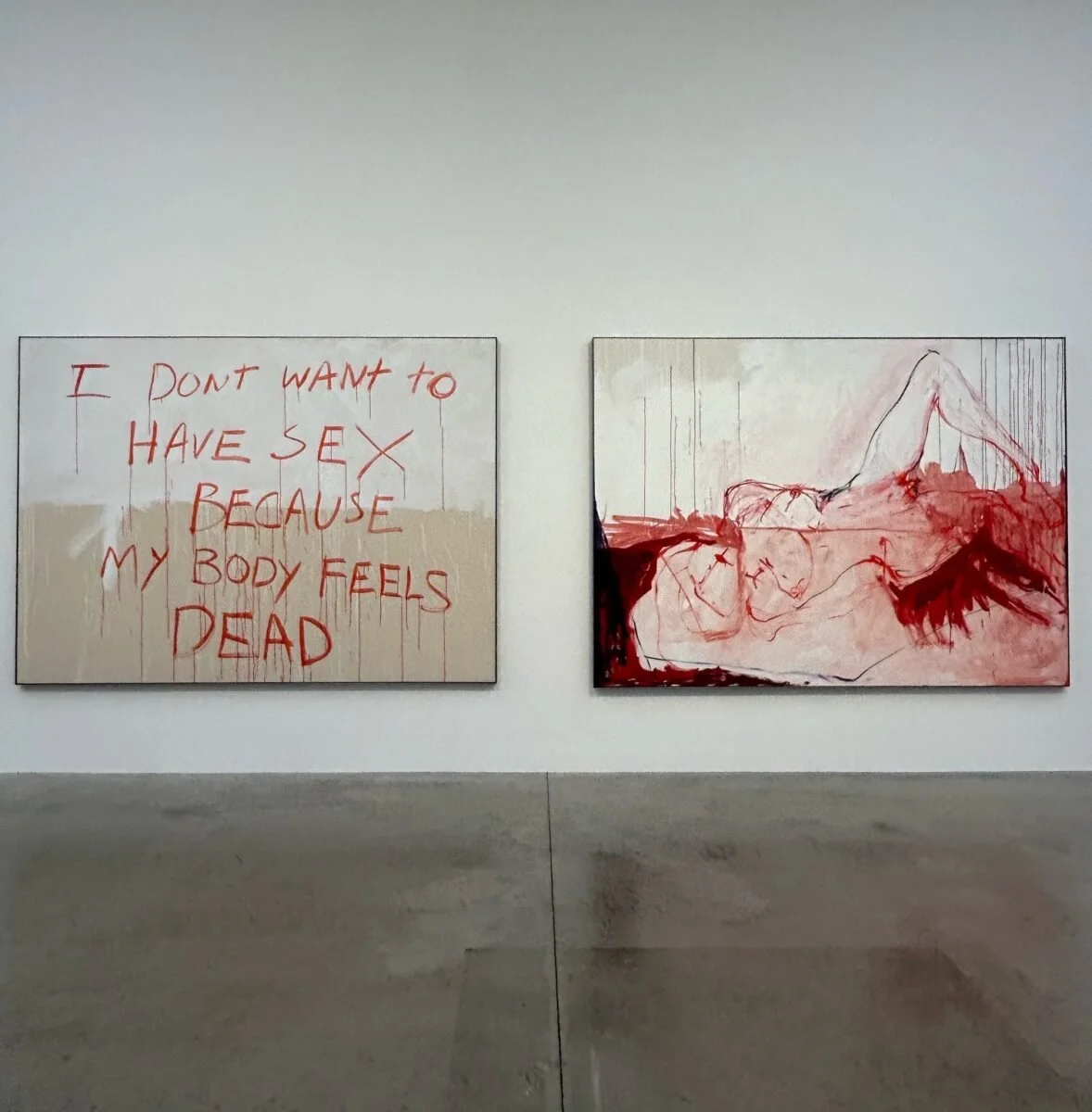

Tracey Emin, in works like My Bed and her autobiographical drawings, offers an antidote to this polished curation. Her self-portrayals, raw, chaotic, vulnerable, challenge the viewer to see her as she is, not as she ought to be. They resist prettiness in favour of honesty. Her line is shaky, urgent, human. In a digital world of filters and symmetry, her work insists on the imperfect body of the broken self, Offered to us in all of its crude rawness.

Works from Tracey Emin’s “lovers Grave” Exhibition 2023

Damien Hirst, on the other hand, often sidesteps the human figure entirely, yet his entire oeuvre is a kind of portrait of modern spectacle. His diamond skull, For the Love of God, is not a face, but it is a self-portrait, one made of wealth, fame, and commodified shock. It mirrors our age precisely: dazzling, immediate, empty at its core yet it mesmerises us into a frenzy of materialism and superficiality which consumes the collective consciousness.

Damien Hirst with his £100 million ‘Crystal Skull’

The Psychological Terrain: Then and Now

What has changed most is not just the tools, but the psychological weight attached to portraiture. Historically, to sit for a portrait was a rare event. One’s image, once rendered, became a legacy. Today, self-representation is constant and compulsive. The portrait is no longer final, it is endlessly replaceable. The anxiety of “being seen” has given way to the anxiety of not being seen enough.

We no longer fear the artist’s gaze, we fear the algorithm’s indifference.

In Van Gogh’s time, the struggle was to be understood. In our time, the struggle is to be visible. Visibility, though, comes at a price. The psychological pressure of constant self-curation breeds insecurity, narcissism, and fatigue. Where once the artist interpreted the soul, now the subject edits it in real time, flattening complexity into aesthetics.

Yet, there is hope. Some contemporary artists push back, embracing slowness, ambiguity, vulnerability. They reclaim portraiture as a space not for performance, but for communion.

Which Era Was More Artistic? A False Question, Perhaps

To ask which era produced more artistic portraits, then or now, is, perhaps ambiguous. Art is not a linear progression of better or worse; it is a mirror, reflecting our collective psyche at a given time. The portraits of the past reveal our longing for permanence. Today’s portraits reflect our fear of being forgotten.

But let us be honest: something has been diluted. Not because digital tools are inferior, they are not. But because the pace of creation and consumption has overwhelmed our capacity for depth. When portraits are made in seconds and scrolled past in milliseconds, the gaze becomes fleeting, distracted, hollow. The quiet, unsettling power of a Sargent or a Van Gogh cannot survive a two-second scroll.

Cindy Sherman Photographic Montage

That said, technology also democratizes. It gives voice to those who were never painted. It allows self-expression for those who were never seen. And some artists, like Cindy Sherman, Zanele Muholi, or even meme-makers in their own right, have used digital tools to critique, subvert, and reinvent the portrait.

Conclusion: The Portrait as Mirror

Ultimately, portraiture whether painted or posted remains a mirror. Sometimes it flatters. Sometimes it distorts. And sometimes, if we are lucky, it reveals.

In the Instagram age, we risk becoming our own caricatures. But art still holds the power to disrupt that loop—to make us pause, to truly see. The challenge now is not the tool, but the intention. For the soul of portraiture to survive, we must remember: to be seen is not the same as being known.

Let us choose the uncomfortable gaze the one that doesn’t flatter, but understands.